Can an AI model teach you how to paint?

Deconstructing the Painting Process

I spend a lot of time in libraries and on YouTube looking at paint-alongs. It's a lot of fun for me to watch how other people "see" an image before they actually start moving paint around. One of my favorites is James Gurney; his ability to break down a complex scene into light shapes and structural volumes is incredible (plus he's one of the few painters I ever see use Casein paints).

But there’s always a slight issue with learning this way, you’re always tethered to the artist's specific subject. If Gurney is painting a dinosaur in a jungle, but I want to paint my coffee mug in the morning light, there’s going to be a pretty stark difference in process. Furthermore, most YouTube tutorials or timelapses are edited for time, not full instructional break downs. They skip or speed through certain crucial parts, like establishing values.

What I’ve always wanted is a system where I could just hand it a photo of my subject, tell it I’m using oil pastels or a pencil, and have it generate a coherent, step-by-step roadmap of how to get there, ideally a machine that creates my own custom painting tutorials.

A new paper out of the University of Trento, Loomis Painter, feels like a very directed step toward that goal. It’s not just trying to generate a pretty image; it’s trying to reconstruct the logic of the painting process itself. The ideas in the paper remind me a lot about the various topics we're exploring at Tio Magic Company in understanding the intersection of AI, content, and art.

Understanding the Data Source

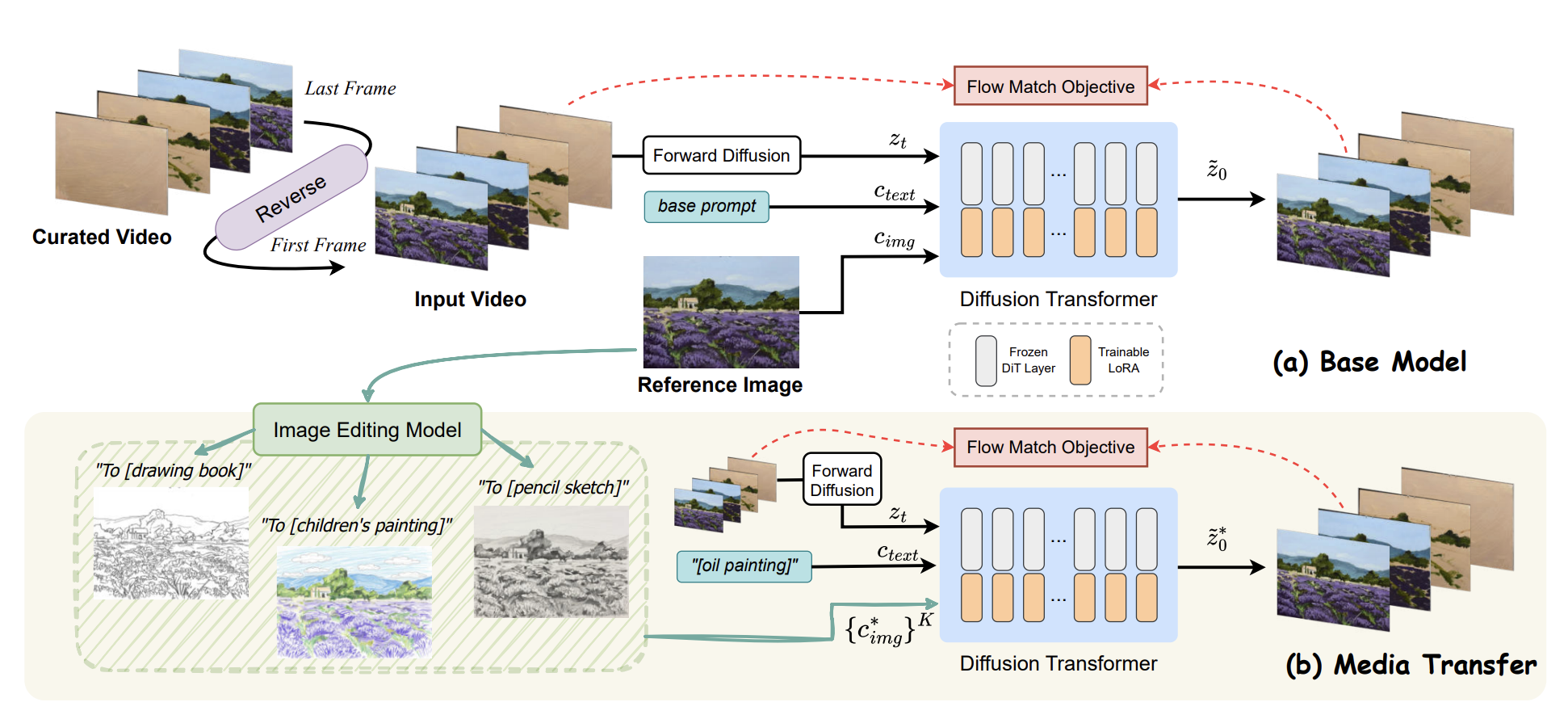

To begin, the authors of Loomis Painter needed data, and if you want to train a model to understand painting, YouTube seems like the obvious place to start. But raw tutorial footage has a problem: the artist's hand is constantly moving over the canvas. If you train directly on that footage, the model learns that "painting" involves a flickering hand blob. It can't separate the evolving artwork from the obstruction.

The solution they came up with was simple and clever. They split each video into 10-second chunks and sample 30 frames per chunk. Then they compute the median pixel value across those frames. Since the hand is moving but the canvas is static, the hand disappears in the median. You're left with just the painting evolution. Add some inpainting for brushes that sit still too long, use GroundingDINO to crop to just the canvas, and they got 767 clean videos where the art appears to evolve by itself.

Learning in Reverse

The most interesting technical choice in the paper is the training direction. Usually, we think of video generation as predicting the future: Start with Frame A, predict Frame B.

But for a painting tutorial, starting with a blank canvas is a "cold start" problem. If you give a model a white square, it has no idea where it’s going. The "meaning" of the first stroke only exists because we know the final destination.

The researchers flipped the logic. They taught the model to "un-paint", to go from a finished artwork back to a blank canvas.

This framing makes the optimization much more stable:

Context is baked in: The model always knows the final goal from the first frame of training.

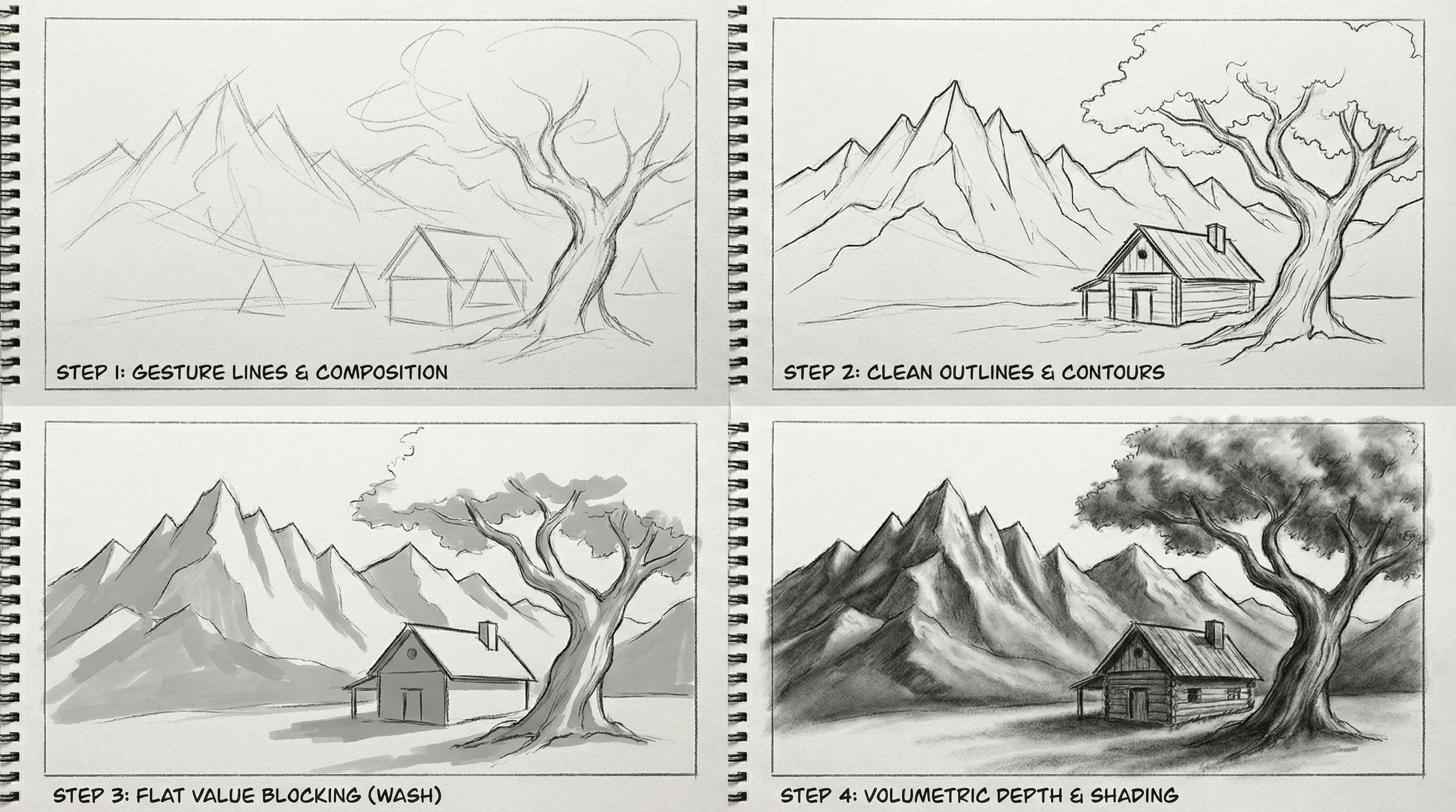

Natural Decomposition: In reverse, the model naturally learns to peel away layers. It removes the fine details (eyelashes, highlights), then simplifies into color blocks, and finally reduces everything to the initial geometric "scaffolding."

When you actually use the model, you just run this learned logic backward. You feed it your photo, and it "constructs" the tutorial from the ground up because it has learned the hierarchy of how images are built.

Process over Style

One thing that separates a real artist from a simple AI filter is understanding the medium. Oil painting is about wet-on-wet blending and layering; pencil sketching is about hatching and pressure.

The researchers didn't want a "style transfer." They wanted a "procedural transfer." They injected textual descriptions (like "pencil sketch" or "oil painting") into the model’s attention layers. By using some clever data augmentation with ControlNet to create variations of the same image in different media, they taught the model that "pencil" implies a specific sequence of strokes, while "oil" implies a different sequence of layering.

It’s mimicking the order of operations, which is the part that actually helps a student.

Measuring the Rhythm of a Painting

How do you evaluate if a tutorial is actually good? Standard metrics like PSNR, which just check if pixels match, don't really apply here. You care about the trajectory.

The authors proposed a "Perceptual Distance Profile" (PDP). They mapped out the curve of how a painting gets closer to the final image over time. Human artists usually follow a specific rhythm: a fast jump in the beginning (laying down the big masses) and a long tail at the end (fiddling with details). They found that Loomis Painter’s "learning curve" closely matches this human rhythm!

The Future

We’re starting to see a shift from "Generative AI" (here is the exact picture you prompted) to what I’d call "Interpretive AI" (here is a process to create what you want).

The code and weights are up on GitHub. It’s still a research project, but the implications for self-learners are interesting. Instead of struggling to apply a James Gurney dinosaur tutorial to your breakfast, you can get a custom roadmap for your specific creative problem.

It’s a nice reminder that the most interesting use of AI might not be replacing the artist, but shortening the distance between a beginner and their first "good" canvas.